From: "Hofman, Bert" <berthofman@nus.edu.sg>

Date: February 2, 2022********* I hope this will be the year in which we overcome the COVID-19 pandemic and restart building a better world for all.

China is determined to do the same, under the banner of “common prosperity.” I wrote about this elsewhere (see here and here) but it is worth revisiting the concept from time to time, as the meaning of it is still in flux. This is not uncommon for China: the leader envisions a new broad policy direction, and then gradually the government and the party fill out the blanks. Deng’s “Reform and Opening up,” Jiang Zemin’s “Three Represents” and Hu’s “Scientific Approach to Development” only took shape over time, and even Xi Jinping’s own “Xi Jinping Thoughts on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era” is still work in progress.

On Common Prosperity, the authorities have made clear that this is not a “tax and spend” policy. It should not, as the Central Economic Work Conference of December stated “create a western-style welfare state.” The mantra has become “to grow the pie before dividing it.”

Be that as it may, there are several reasons why more taxes are needed. First, China’s changing society with a growing middle class demands more services, some of which will have to be supplied by government. Second, China’s rapidly aging population will place huge demands on the government’s coffers for health care and pensions. Some estimates put the additional costs of those alone at some [10 percent of GDP] by 2050 due to aging alone.

There is also common prosperity itself, as the promised equalization of services across China requires more resources, and the growing of the middle class may imply that government needs to take on more burden, for instance by deepening health insurance and reducing out-of-pocket costs. Much of the additional spending burdens will go to local governments, which deliver most of government services, and which have been strapped for resources for some time, so much so that the “backdoor,” the local government financing vehicles, seems wide open again.

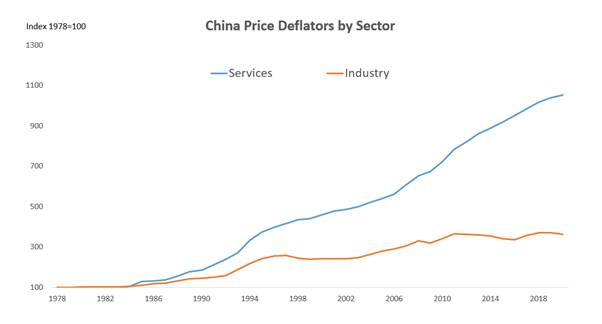

Then there is the dismal science, economics. The Baumol effect, which says that due to differences in technical progress between services and manufacturing, over time services become more expensive. Baumol is alive and well in China (Figure 1) and thus one can expect that even without additional tasks, government will take a bigger share of GDP—which requires more revenues. Wagners law says that government spending goes up in leaps, not gradually, in particular after crises. The COVID-19 crisis may just be such a leap point, as it is for most of the western world.

Figure 1: Baumol in China

Source: NBS via CEIC data

Unfortunately, in recent years China’s government revenues have been declining as a share in GDP. In part this has been driven by policies, all with good intentions—a reduction of the VAT, inclusion of the business tax in the VAT, exemption of small enterprises from VAT, a move to a consumption-based VAT, an increase in the VAT export credit, a reduction in the corporate income tax for small enterprises and tax free shopping in free ports all have chiselled away at the tax base. Some measures, such as VAT exemption, have also made tax administration harder.

The bottom line is that China’s tax to GDP ratio, which saw a steady rise after the 1994 fiscal reforms, peaked back in 2016 at some 23 percent, and has since come down to below 20 percent of GDP. This decline contributed almost half of the increase in the augmented government deficit (see, among others, the recent IMF Article IV on China). Given the spending pressures yet to come, and the increasingly high debt levels of especially local governments, raising more taxes is an important, and increasingly urgent matter.

So what would be good taxes to cover China’s future government spending?

Comparing China’s tax structure internationally (Figure 2) show that China’s tax take is still well below the average of OECD countries in total revenues, though it has already surpassed the average for the Asia-Pacific.

Second, what stands out is China’s heavy reliance on Value Added Tax, which at 6.7 percent of GDP equal that of OECD countries and make up a third of tax revenues excluding social security. Other taxes on goods and services, mainly excise taxes on “bads” such as alcohol and cigarettes, and luxury goods, make up another 2.4 percent of GDP.

Third, social security premia, at 6 percent of GDP, are still 3 percentage points of GDP lower than the average OECD country, but well above the average of the Asia-Pacific. They are undoubtedly set to rise, as pension funds are increasingly strained, and health insurance is still shallow. Moreover, only urban workers are currently covered by unemployment insurance, which became an issue during COVID-19: because many migrants were not covered, consumption cratered, and government had to step in with a stimulus to keep growth going.

Finally, and strikingly, China’s revenues from personal income tax are only 1.1 percent of GDP, and make up only 5 percent of total revenues, compared to 20 percent of total in OECD countries, more than 40 percent for the United States and Australia, and even more than 50 percent for Denmark.

Figure 2: The Tax Man Cometh

Source: OECD Tax Statistics and Asia Pacific Tax Statistics, online version, accessed 30-1-2022

Though China’s personal income tax is progressive, and its highest marginal tax rate is, at 45 percent, relatively high, there are few that actually pay it. Also, important income categories for the better off, such as dividends and interest, are lightly taxed at 20 percent, whereas capital gains are not taxed. The exception to the latter is capital gains on real estate, tax at 20 percent but individuals generally are exempt if they have occupied the residence for at least five years. China also does not tax inheritance, another source of redistribution in some OECD countries.

The heavy reliance on VAT is a very efficient way of taxing, but it also means that the poor, who spend a large share of their income on consumption, are disproportionally taxed. In most OECD countries, the personal income tax more than compensates for this undesirable distributional effect, but not in China. No doubt this will change in the years to come, as Common Prosperity cannot avoid looking deeper into the distributional effects of China’s taxes.

In that context, a tax on real estate has been much debated in China. Two pilots, one in Shanghai and one in Chongqing have been under way for some time, and several other cities were to be added according to the pilot this year.

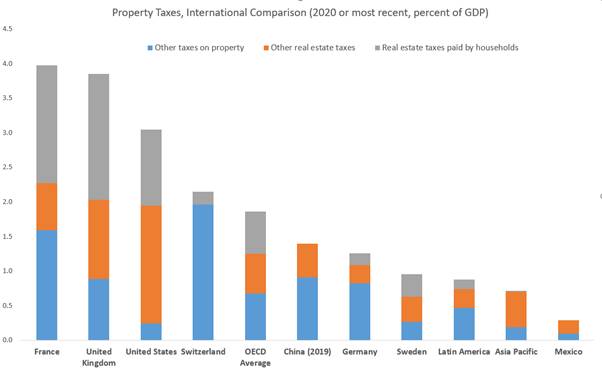

China does tax property at a level comparable to that of OECD countries (Figure 3), but Chinese households do not pay any real estate tax (or "recurrent taxes on immovable property" as the OECD parlance goes). China actually taxes real estate already with a variety of taxes (a house tax on firms operating properties, an urban maintenance tax, stamp duty, a deed tax and land appreciation tax) and together they make up some 8 percent of total taxes in China, higher than the average OECD countries. None of these taxes, though, classify as a real estate tax on households currently under debate.

A real estate tax on households is a good tax for local governments according to the “bible” of local government finances. It is a relatively stable source of revenues, and there is a good correspondence between those that pay the tax and those that benefit from the services a local government provides. The tax would also be vastly superior to the current dominant source of revenues—land sales. That source is highly pro-cyclical, pushes local government to excessive land use, and, as we have seen in 2021, ties in local government revenues (and spending) with the vagaries of the real estate sector. Given that richer people usually own more property in China, taxing real estate would also contribute to a fairer tax burden overall.

The best time to introduce a household real estate tax has come and gone. If it would have been done in the mid-1990s, along with the major overhaul of tax and intergovernmental fiscal system that took place, it would have been before the privatization of urban housing in the second half of the decade, and few would have objected. Now is different: most urban residents own long term leases (up to 70 years), and political resistance of the urban middle class is not something the government can easily ignore.

Figure 3: Taxing property

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics, online version, accessed 30-1-2022

There are several objections analysts in China raise against a real estate tax. First, people believe they have already paid for their house lease, and thus a tax would be unfair in this view. This is true, but it is true for any tax raised—some will lose out compared to a situation without tax.

Second, many argue that Chinese people really are renting, not owning their property, and thus a real estate tax would be inappropriate. This does not hold much water—many countries (including the UK and the Netherlands) tax both owners and occupiers of a property. A VAT on services is not much different—you pay tax on the services derived, not from buying a good.

Third, people may not have the cash to pay the tax. Many people with limited income are nevertheless real estate millionaires. They received their apartments at very low costs in the 1990s, and since then their housing value has skyrocketed, whereas incomes have increased only gradually. Even a modest real estate tax rate could take most of a retiree’s income.

The government could decide these people should sell and move to cheaper places (as Russia did when it introduced a real estate tax) but this could cause significant unrest, something the authorities do not like. On the other hand, China’s mortgage market could help out here. Twenty years ago it was hard to get a mortgage, but today, house owners could take out some of the increase in value to pay for a property tax by means of a mortgage or topping up of an existing one.

Fourth, imposing a real estate tax could significantly drive down the value of housing. In theory, the value of a house would fall by the discounted value of future taxes, which can be significant, more so in a situation like China, where real estate value increase have outpaced real interest rates (and thus taxes due in future outpace the discount rate). Introducing a real estate tax at a time when the housing market is already in turmoil, and some developers are in trouble may not be optimal. It is no surprise that the government’s plans to mainstream the real estate taxes currently piloted in Shanghai and Chongqing were put on hold for now. According to Caixing, the city of Xiamen first announced a pilot, but then withdrew the plans.

So what to do?

One option could be to start with real estate taxes on new housing first. The idea would be that any house from a development that is yet to begin would be taxes at the desired rate. This would mean that prices for new houses would go down, as buyers will know in advance they need to pay taxes in future. Consequently, also the price of land would go down, as developers know house buyers will pay less for their housing. And instead of the revenues from one-off sale of land, local governments would receive a reduced land price and a future stream of tax revenues.

Somewhat surprisingly, introducing the tax in such a way could be very popular with buyers, because the upfront costs of housing will drop—they pay part of the price over time by means of annual taxes. Prospective home owners have to pay a very high down-payment on housing and many do not qualify for a mortgage. So paying less up front and more over time would certainly be welcome. In fact, as an aside, it could reduce China’s famously high household saving rate, much of which is to save for housing, and the measure could thus boost consumption.

It will no doubt be less popular with local government, who have been living off the abundant land revenues that, according to the IMF, add some 3-3.5 percent of GDP to revenues every year (some estimates even put the number at 6-7 percent of GDP). Would they be even more strapped for cash then?

Not necessarily. Here, the bonds market can help out local governments, at least the ones that manage their affairs responsibly. The future stream of real estate taxes can be the collateral for local government bonds. All that central government needs to do is to allocate more bond quota to those local governments that have introduced a real estate tax.

So what about existing housing? For reasons of equity as well as efficiency, they should not be ignored, at least not forever. Here, China can make use of its “Chinese characteristics” which means that the State owns all the land, and house-owners are merely leasing for a specific period of time. China could consider imposing a real estate tax for houses that have come to the end of their land lease. The length of the leases handed out in the past varies, and started with 20, 30 and 40 year leases, and were then gradually extended to 70 years. Some of these leases are now falling due.

At least in theory, government is free to take back the land after expiration of the lease, but back in 2017, premier Li Keqiang assured lease holders that these would be extended. Up to now this has been done for free or for a low fee. Instead, government could consider imposing a real estate tax after lease renewal. Current owners will not be pleased of course, but paying a tax is much better than losing the property altogether!

If done so, then gradually over time all of China’s housing will pay a real estate tax. Growing out of the Plan was how economist Barry Naughton once describes China’s reform trajectory. This proposal would be Growing into the Real Estate Tax.

Even if the Chinese authorities manage to introduce a real estate tax for households (and that is a big if) expectation on revenues should be modest. On average, OECD countries raise 0.6 percent of GDP in revenues from real estate taxes on households. Even in the US, which has a long tradition of real estate taxes, this is only 1.1 percent of GDP. The UK holds the record with 1.8 percent of GDP.

In Shanghai and Chongqing, the pilots for the real estate tax, real estate taxes did go up as a share of total taxes, but even there all property taxes (new and old) only make up only 5 percent (Shanghai) and 3.5 percent (Chongqing) of total revenues, according to Caixing. So while a real estate tax is welcome for other reasons--notably to wean China's local governments off land revenues and excessive land use, it will not be enough to solve China’s revenue problem.

What else could be done?

One option could be a local surcharge on the personal income tax, as is done in countries like Denmark. The US also has a subnational income tax. Such a tax would be a good local tax, in that tax payers and beneficiaries closely correspond. The tax surcharge is likely to be more variable than a real estate tax, but much more stable than land revenues. If administered alongside the national personal income tax, it would be much easier to administer than a real estate tax. Most importantly, such a surcharge would contribute to China’s goal of common prosperity.

The bottom line is that a gradual phasing in of a property tax, complemented with a local surcharge on personal income tax (i) would increase the revenue base of China’s government; (ii) would in particular help local governments, which have experienced the largest spending pressures; and (iii) would contribute to Common Prosperity. More needs to be fixed in China’s fiscal system, but this package would be a good start!

***********************

Bert

Bert Hofman

Director, East Asian Institute

Professor in Practice, Lee Kuan Yew School

National University Singapore

469A Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 259756

+65-65165067

Twitter: @berthofmanecon

YouTube: https://tinyurl.com/nhskrv4n

You received this message because you are subscribed to the Google Groups "China Security Analysis Group" group.

To unsubscribe from this group and stop receiving emails from it, send an email to Zhongan+unsubscribe@googlegroups.com.

To view this discussion on the web visit https://groups.google.com/d/msgid/Zhongan/EEA980B2-A667-44C3-AA2A-CFA407F67528%40gmail.com.